The long march toward racial equality in the ranks

The late Colin Powell was only 11 years old when President Truman issued an executive order ending segregation in the armed forces. “I and so many men and women of color who have served this nation in uniform owe so much to President Harry S. Truman and to Executive Order 9981,” Powell said in 1998.

It was in 1948 that Truman issued the order, saying, “There shall be equality of treatment and opportunities for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, creed or color.”

But first, the man from Independence, Missouri, had to overcome his upbringing. Both of Truman’s grandparents had owned slaves prior to the Civil War, and he said his own mother had died “an unreconstructed rebel.”

Kurt Graham, director of the Truman Library, says the archives contain handwritten examples of his racist views, such as his 1939 letter describing the movie “Man About Town,” starring Jack Benny and Eddie Anderson: “It is a very funny show. The N-word steals the screen.”

“No hesitation, no compunction about using a racial epithet like that,” said Graham.

Six years later, as World War II entered its final agony, Truman was thrust into the presidency by the sudden death of Franklin Roosevelt, and found himself the commander-in-chief of two armies – one Black, and one white.

Charles Bowery, director of the U.S. Army’s Center of Military History, called the war “a watershed moment in the process of segregation.” He said the one million African Americans who fought for freedom in uniform while being denied it at home exposed the hypocrisy of segregation. “It forwarded the civil rights movement, because of the massive scale of service of African Americans in uniform,” he said. “It just could not be ignored. You could not ignore the bravery of African Americans.”

And Truman could not ignore the despicable treatment of Black veterans, like Isaac Woodard, a soldier who came home from the war, and was dragged from a bus by South Carolina police and beaten so severely that he permanently lost his sight.

Graham said, “Truman, I think, just says, ‘That’s enough.’ He instructed the Justice Department to investigate. An all-white jury acquitted the defendants, and life went on in South Carolina. But Harry Truman was not gonna let that stand.”

CBS News

Speaking at the Lincoln Memorial, on June 29, 1947, Truman became the first president ever to address the NAACP. He proclaimed, “There is no justifiable reason for discrimination because of ancestry or religion or race or color.”

Risky politics, for a president seeking a second term. According to Graham, Truman’s political future in 1948 was “on the ropes. He was seen to be someone who likely was not going to win re-election.”

Days after he was nominated, Truman issued the order to end segregation in the military. According to Bowery, the Army’s reaction to the order, particularly in its leadership, was stridently opposed.

Truman appointed a committee headed by Charles Fahey to enforce the order. Records show its staff director warning Fahy, “The Army intends to do as little as possible” – and might have gotten away with it, except for a Black civilian who worked at the Pentagon.

Roy Davenport is one of history’s hidden figures, using his inside knowledge of the Pentagon’s personnel practices to show the Fahy Committee the Army’s response for desegregation “wasn’t worth the paper it was written on.”

But what really turned the coin, said Bowery, was the Korean War. “Desegregation begins in foxholes in Korea.”

With all-white combat units retreating in the face of the North Korean onslaught, Black soldiers were sent in to fight alongside whites. “What happens is that these units turn the tide,” Bowery said, “and the Army in Korea is on a path to integration, because they have finally and completely disproven this idea that Black soldiers cannot be trusted alongside white soldiers.”

National Archives

As the buildup to war in Vietnam was beginning, and the civil rights movement was reaching critical mass, Joe Anderson was a cadet at West Point.

Martin asked him, “Did you ever wonder to yourself, ‘What am I doing here?'”

“I absolutely wondered why I was at the Academy, when all of our people of Black heritage were sitting in at counters and fighting to be treated fairly in the United States,” Anderson replied.

James Fowler, one of only six Black colonels in the entire Army at the time, gave Anderson this advice: “He said to me, ‘Joe, we have a lot of people that can sit in at counters. We don’t have a lot of people that can get through West Point. That’s your job.'”

As he entered his senior year, Anderson was denied a leadership position in the Corps of Cadets. “My view is that the Academy in 1964 was not ready to have African Americans demonstrate significant leadership in the parades and that kind of thing,” he said.

CBS News

But two years after graduating, Anderson became arguably the best-known soldier – Black or white – in the entire Army, as leader of “The Anderson Platoon,” subject of an Oscar- and Emmy-winning documentary that aired on CBS. He said, “It was probably the first time that Americans had seen an African American in leadership in combat.”

“Anderson’s Platoon” showed the country what the Army had learned in Korea. “In combat, it’s about who can get them home safe,” Anderson said.

But in the rear areas, race still mattered.

At age 19 Hank Thomas was one of the original “Freedom Riders.” “A firebomb was thrown through the back window of the bus,” he recalled. “And when I was getting off the bus, I was attacked again physically. Each physical blow was a badge of honor.”

Sure that he was about to be drafted into the Army for his trouble-making, Thomas volunteered to become a medic, and was sent to Vietnam. There, he said, the commanding officer was a captain from Mississippi, and the supply sergeant was a redneck from Mississippi.

“There was a group of soldiers in my outfit who flew the Confederate flag,” Thomas said. “I tore the flag down, and dared anyone to put it up again.”

“Did you have any run-ins with that redneck supply sergeant?” asked Martin.

“The Black soldiers came to me and said the sergeant was not giving them new boots, so I went over to the supply shack, threatened to whip his butt,” he replied. “I almost got court-martialed for it, but I got the boots and the equipment for the Black soldiers.

“Black soldiers were not going to take the same kind of treatment that they had taken in civilian life,” Thomas said.

After Vietnam, the U.S. abandoned the draft, and created an all-volunteer force, which attracted recruits by offering better pay and benefits. “What it did was dramatically increase the number of African Americans who raised their hand to serve,” said Bowery.

CBS News

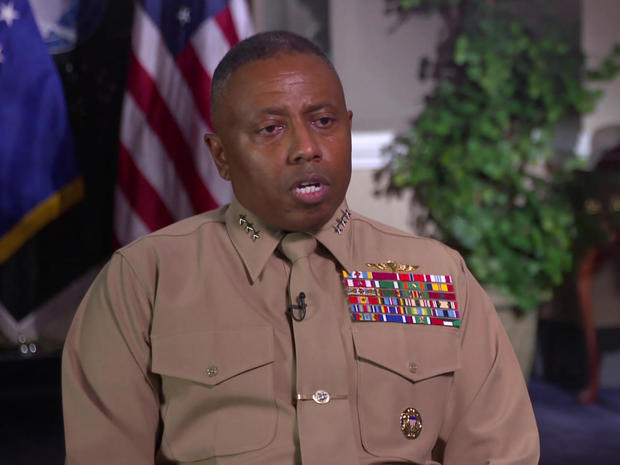

Now a lieutenant general, Dimitri Henry joined the Marines in 1981: “Because I was 17, my mother had to sign for me to go in and serve. Forty-one-and-a-half years later, here I sit.”

Martin asked, “Did you experience anything that felt like discrimination as you were coming up through the enlisted ranks?”

“I would call it points where individuals would show their disdain for someone who looked like me,” Henry said. “The typical name calling,” including the n-word.

How’d you react? “I chose not to react,” he said. “If you’re going to allow someone else to control your emotions, then you’ve already lost.”

While Henry was still a sergeant, in 1989, Colin Powell became the first Black Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. During the first Gulf War against Iraq, Powell showed the nation a Black general in charge.

But Henry said he still feels judged by the color of his skin. “It helps me to focus more, because I understand what is being thought about me and what people may decide to do just based solely on what I look like,” he said.

“That sounds like a ‘I’ll show them’ attitude,” Martin said.

“Unfortunately, I think that’s exactly what it is,” he replied. “It’s a survival type of tool.”

Henry survived, to become the director of intelligence for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, another first for Black Americans in uniform. “That happened on the backs and shoulders of others that have gone before, and it just builds and builds and builds,” he said.

CBS News

The most obvious result of the forces that President Truman set in motion 75 years ago is Lloyd Austin, the first African American Secretary of Defense. When asked if he would be in this job without that executive order, Austin replied, “Probably not.”

And in the two years he has been in the job, Austin has more than doubled the number of Black three- and four-star generals, from 10 to 22. And the criteria was simple: “We selected them because they’re the best people for the job.”

It’s been 75 years since Truman issued his executive order. Martin asked, “Is there equal treatment and opportunity in the armed forces?”

“If you ever stop striving to achieve that goal of equal opportunity and equal treatment,” Austin replied, “I think then you’ll begin to slide backwards.”

For more info:

Story produced by Mary Walsh. Editor: Carol Ross.

See also:

For more latest Education News Click Here