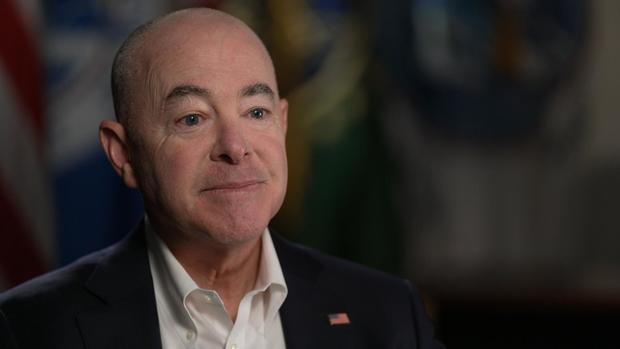

Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas won’t call immigration at southern border a crisis

When he was less than a year old, Alejandro Mayorkas and his family came to the United States as refugees, fleeing Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba. Today, he is the first immigrant to head the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. His portfolio includes everything from counterterrorism and cyber-security, to overseeing the Coast Guard and Secret Service. But it’s what he’s done – or not done – about the large number of migrants crossing the U.S. border with Mexico that’s prompted protests by migrant advocates…and fiery attacks by Republicans who want to impeach him. Tonight, you will hear from Secretary Mayorkas about the efforts to push him out of office and why he refuses to call the situation on the southern border a “crisis”.

Early morning is often the busiest time for illegal crossings along the U.S.- Mexico border.

The day we went out with the U.S. Border Patrol near El Paso, Texas was no exception.

Before meeting the Cabinet secretary in charge of securing the borders, we got a view from the field.

The Border Patrol reported over 2 million apprehensions in the past year – a record high. Some migrants surrendered themselves to border agents, with the intention of seeking asylum.

60 Minutes

But the DHS estimates another 600,000 people evaded agents and entered the U.S. illegally, the highest number in over a decade.

Which is why Secretary Mayorkas’ testimony before Congress last fall raised a few eyebrows

Sharyn Alfonsi: What the American people see is a border that looks to be chaotic, that looks to be porous.

Alejandro Mayorkas: Well, let, let’s, I mean, the number of people that are arriving at our border is at an extraordinary height. There’s no question about that. But that is not unique to the southern border of the United States. There is a tremendous amount of movement throughout the hemisphere and in fact throughout the world.

Sharyn Alfonsi: The chief of the border patrol, Raul Ortiz, testified before Congress that some areas of the border are in a crisis situation. Do you agree?

Alejandro Mayorkas: I think that we face a very serious challenge in certain parts of the border.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you view what’s happening right now on the border as a crisis?

Alejandro Mayorkas: I view it as a significant challenge.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Why won’t you say the word ‘crisis?’

Alejandro Mayorkas: You know what? Because I have tremendous faith in the people of the Department of Homeland Security. And a crisis speaks to me of a withdrawal from our mission. And, and we are only putting more force and more energy into it.

A lot of force and energy is now being directed at Secretary Mayorkas on Capitol Hill.

This past week, Republicans took aim at the secretary, blaming him, personally, for the drug deaths of Americans, the rape of migrant children and more.

60 Minutes

Sharyn Alfonsi: Congress seems to be more interested in impeaching you than passing immigration reform. One member of Congress said he’d like to arrest you for negligent homicide for the deaths of young people from fentanyl, another compared you to Benedict Arnold.

Alejandro Mayorkas: I disregard that type of rhetoric. I’m focused on the mission.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you think they’re just trying to get you to resign?

Alejandro Mayorkas: I’m not going to resign. I love public service. I think it’s an incredible honor to be a part of it.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How often do you and President Biden discuss the situation at the border? There’s a perception that the president doesn’t wanna talk about the border.

Alejandro Mayorkas: That’s a false impression that I, I consider to be also political rhetoric. I was with the president when he visited the border. I’ve spoken multiple times with the president. I, of course, speak with the White House team on a regular basis and with my colleagues in the Cabinet.

The problems at the border didn’t start with the Biden administration and likely won’t end with it. Congress hasn’t passed major immigration reform in nearly three decades. Secretary Mayorkas is asking Congress for additional resources on the southern border.

Alejandro Mayorkas: This is the first year, since 2011, that we have added to the Border Patrol 300 more agents. The fiscal year 2024 budget calls for 350 more Border Patrol agents, more than $100 million in technological investments.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is there anything that’s off the table, that you won’t do to secure the border?

Alejandro Mayorkas: Well, the president– as– I think you know very well, said we are not going to construct more wall that costs billions and billions of dollars, that is immovable and that is already beginning to corrode.

Secretary Mayorkas joined the Biden Administration with a resume seemingly well suited for the job. He’d been the top federal prosecutor in Los Angeles and deputy director of Homeland Security under President Obama. He was also a refugee whose Romanian mother and Cuban father fled Cuba when he was an infant.

Alejandro Mayorkas: I understand deeply the yearning of parents to give their children opportunities that America offers. We are a nation of laws. If people qualify under the law, then we embrace them. If they don’t, then we return them.

Sharyn Alfonsi: The first weeks in office, the Biden administration halted deportations for 100 days, stopped all border wall construction, and suspended the Remain in Mexico policy. Critics say it all added up to putting a come in, we’re open sign on the door.

60 Minutes

Alejandro Mayorkas: I don’t think that the more than a million people last year that we removed or expelled would consider the border open.

Sharyn Alfonsi: But the messaging

Alejandro Mayorkas: But

Sharyn Alfonsi: Was the messaging wrong there that, you know, we’re open?

Alejandro Mayorkas: That wasn’t our messaging. But that was the

Sharyn Alfonsi: But that’s what

Alejandro Mayorkas: The messaging

Sharyn Alfonsi: The migrants were getting.

Alejandro Mayorkas: Because remember something, that we are not the only source of messages that the migrants receive. We have smuggling organizations that exploit the migrants. And those smuggling organizations engage in mis and disinformation.

In December, according to Border Patrol figures, an average of 1,800 migrants a day crossed the border into the El Paso area, overwhelming the city.

To manage the increasing flow of migrants from crisis-stricken Nicaragua, Haiti, and Cuba, President Biden expanded the use of a public health law known as Title 42, invoked during the pandemic, to expel migrants to Mexico.

At the same time, the administration unveiled new pathways for migrants to enter the U.S. legally.

All the people in this line at a border crossing in El Paso scheduled an appointment with U.S. Customs and Border protection by using a mobile app called CBP One.

Carla Delgado, from Venezuela, told us her family had crossed the Darien Gap, a dangerous stretch of jungle straddling Panama and Colombia, to get here.

After a series of background checks and screenings, they were granted permission to temporarily enter the United States.

By early afternoon, they enjoyed their first slice of pizza in America. They have friends in Chicago and told us they plan to build a new life there and apply for asylum in the U.S.

60 Minutes

Sharyn Alfonsi: There’s a backlog in the immigration system. We know only years from now will a judge figure out whether they actually qualify for asylum in the U.S. How is that arrangement good for them? How is that arrangement good for the country?

Alejandro Mayorkas: I would ask them after they enjoyed their f– their first pizza. How do they feel as compared to what they fled? You mentioned that their asylum claim may not be adjudicated, may not be judged for years. Our asylum system is broken. We need Congress to fix it.

The new policies have reduced the number of migrants crossing into the U.S. in January and February, but created a bottleneck on the other side of the border.

In Juarez, Mexico, Monday night, a fire at a migrant detention center killed at least 38 men from Central and South America.

Days earlier, at this women’s shelter, we met families who’d been stuck in Juarez, for months.

Every morning at 9 a.m., women frantically try to refresh the government app hoping to get an appointment to enter the U.S.

We watched with Karina Breceda who runs the shelter.

By 9:05, all the appointments, and hope, were gone.

Karina Breceda: It’s lottery with people’s lives: with, with people’s families, with people’s livelihoods, with people’s well-being.

Sharyn Alfonsi: The Biden Administration says this is more humane than what was going on before.

Karina Breceda: It is not ‘the most humane’ process because the most vulnerable aren’t, aren’t getting access to it.

60 Minutes

Like Guadalupe Vazquez. She told us her husband had been murdered in southwest Mexico, and one of her sons had been shot in the eye and needed bullet fragments removed.

She said she’s been trying for two months to get an appointment to legally enter the U.S.

Guadalupe (translation): I’m willing to wait to get an appointment, even if it takes long, but I’m going to make it.

Sharyn Alfonsi: If you’re not able to get an appointment on the app, h– what’s your plan?

Guadalupe (translation): I’ll try to cross with a smuggler, and I’ll cross with my children.

We saw more desperation outside a nearby cathedral. Cristina Coronado runs a food program there.

Cristina Coronado: (translation): Juarez is in a moment of crisis. More than 10,000 migrants are now in the city. And most of them are sleeping in the streets.

Sharyn Alfonsi: As people wait here, are they getting frustrated?

Cristina Coronado: (translation): Very frustrated… very angry… very confused…

These men told us they’d been trying in vain for weeks to get an appointment on the CBP One app.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Oh, yeah. And it gets stuck, right?

Man who speaks English: All people see, one opportunity at 9 o’clock. No more. Five minutes. No more. Try again the next day.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You have to wait for tomorrow?

Man who speaks English: Tomorrow, tomorrow

Sharyn Alfonsi: We were in Juarez and we’re surrounded by a group of migrants. Everybody’s holding up the app, pointing to it saying, ‘It’s not working. It’s not working.’ And there’s frustration. And the numbers are growing.

Alejandro Mayorkas: Well, there’s

Sharyn Alfonsi: And the numbers are growing.

Alejandro Mayorkas: I will not represent to you, Sharyn, that it is flawless. But remember something: that to, to build a safe and orderly way, and we are continuing to build that, remember where we were two years ago.

The Biden Administration has reunited more than 600 children that were separated from their families at the border during the Trump administration. But now, the secretary is facing what could be another defining moment for the country.

On May 11th, Title 42, the pandemic-era public health order, will expire. That means without some new arrangement, the only illegal border crossers the U.S. could expel to Mexico would be Mexicans. Thousands of migrants are waiting at the border and thousands more are arriving every day.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Has Mexico agreed to take back non-Mexicans if Title 42 ends?

Alejandro Mayorkas: So we are in discussions with Mexico with regard to how they will handle any increase in the number of individuals seeking to migrate north.

Sharyn Alfonsi: If Mexico doesn’t accept other nationals, then what?

Alejandro Mayorkas: Well, we have all sorts of contingencies. I mean, that’s what we do.

Sharyn Alfonsi: It’s going to be complicated. It’s going to be expensive.

Alejandro Mayorkas: It is going to be complicated; it is going to be expensive. This has been complicated, expensive, and challenging for decades.

Produced by Andy Court. Associate Producer, Annabelle Hanflig. Associate Producer, Camilo Montoya-Galvez. Associate Producer, Julie Holstein. Broadcast Associate, Elizabeth Germino. Edited by Joe Schanzer.

For more latest Education News Click Here